Books

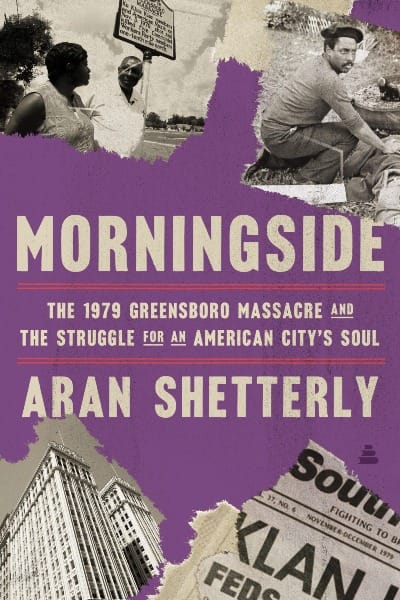

MORNINGSIDE: The 1979 Greensboro Massacre and the Struggle for an American City's Soul, Amistad (October 15, 2024)

Find links to order Morningside here.

To dig deeper on MORNINGSIDE and learn about sources, and to access teacher materials, info for Book Clubs, photos, and interviews with the author, click here.

"MORNINGSIDE is a riveting account of a critical chapter in our nation's racial history. Aran Shetterly takes us along for a wild ride – Nelson and Joyce Johnson’s decades-long struggle to achieve justice for America’s poor and marginalized who are living on the 'outskirts of hope.' From the Klan's deadly ambush, to the quest for truth and reconciliation, to the building of beloved community, the Johnson’s story is an essential – and moving – lesson in the courage it takes to transform tragedy and despair into resilience and hope, all in the pursuit of justice."— Michelle Alexander, author of the iconic bestseller, THE NEW JIM CROW

An unflinching look at the all but forgotten, though no less shocking 1979 racial tragedy that divided Greensboro, N.C., and the nation, and the grassroots activists who, in their tireless fight for justice, refused to give up on America’s promised ideals.

On November 3, 1979, as activist Nelson Johnson assembled people for a march adjacent to Morningside Homes in Greensboro, North Carolina, gunshots rang out. A caravan of Klansmen and Neo-Nazis sped from the scene, leaving behind five dead. Known as the “Greensboro Massacre,” the event and its aftermath encapsulate the racial conflict, economic anxiety, clash of ideologies, and toxic mix of corruption and conspiracy that roiled American democracy then—and threaten it today.

In 88 seconds, one Southern city shattered over irreconcilable visions of America’s past and future. When the shooters are acquitted in the courts, Reverend Johnson, his wife Joyce, and their allies, at odds with the police and the Greensboro establishment, sought alternative forms of justice. As the Johnsons rebuilt their lives after 1979, they found inspiration in Nelson Mandela’s post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Martin Luther King Jr’s concept of Beloved Community and insist that only by facing history’s hardest truths can healing come to the city they refuse to give up on.

This intimate, deeply researched, and heart-stopping account draws upon survivor interviews, court documents, and the files from one of the largest investigations in FBI history. The persistent mysteries of the case touch deep cultural insecurities and contradictions about race and class. A quintessentially American story, Morningside explores the courage required to make change and the evolving pursuit of a more inclusive and equal future.

I am grateful for the support this project received from Virginia Humanities, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Virginia Center for Creative Arts.

REVIEWS of MORNINGSIDE

"In this brilliant investigative deep-dive, historian Shetterly revisits the 1979 slaying of five radical...activists by the KKK during an anti-Klan protest in Greensboro, NC. [Shetterly] expands his story into a history of the FBI's extensive COINTELPRO-era use of informants in white supremacist groups...Propulsive and precise, this brings into startling focus the freewheeling world of law enforcement's Cold War-era anticommunist crusade." – Publishers Weekly, starred review

"The author masterfully ... construct[s] a detailed, nuanced, and gripping narrative that describes all of the principals’ motivations, struggles, and aims." — Kirkus Reviews

"Shetterly adds a significant contribution to the literature on this topic by adeptly using public files, including video, intensive in-depth interviews with more than 70 people, and FBI and court records from state and federal trials spanning 1979 to 1984...The author methodically disassembles competing and self-serving accounts [and] gives readers a compelling narrative of personal stories about the 1979 Greensboro massacre and its legacy in the context of Greensboro’s history, the Black liberation movement, and political and revolutionary aspirations to end the nation’s racial disparities and exploitation of the working poor." – Thomas J. Davis for Library Journal

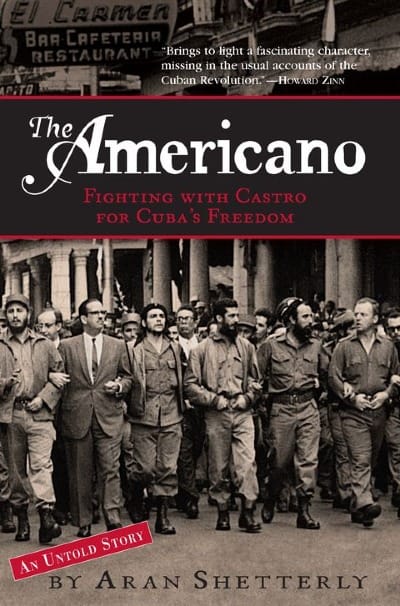

THE AMERICANO, Algonquin Books (2007)

Get a copy of The Americano here.

When William Morgan was twenty-two years old, he was working as a high school janitor in Toledo, Ohio. Seven years later, in 1958, he walked into a rebel camp in the Cuban jungle to join the revolutionaries in their fight to overthrow the corrupt Cuban president, Fulgencio Batista.

The rebels were wary of the broad-shouldered, blond-haired, blue-eyed Americano—but Morgan’s dedication and passion, his military skill and charisma, led him to become a chief comandante in Castro’s army. He was the only foreigner to hold such a rank, with the exception of Che Guevara. Based on interviews with his friends, family, and former fellow rebels, as well as FBI and CIA documents, this is the remarkable story of his journey—and how it ended in 1961, when at the age of thirty-two, he was executed by firing squad at the hands of Fidel Castro.

Watch PBS's American Experience documentary American Comandante in which I appeared to talk about William Morgan's life, his time in Cuba, and J. Edgar Hoover's obsession with keeping him from being viewed as an American hero and democratic freedom fighter.

REVIEWS of THE AMERICANO

Publishers Weekly's starred review of THE AMERICANO: Fighting with Castro for Cuba's Freedom stated: "William Morgan, an American who made his way to the front line of Castro's revolution in Cuba, gets thorough and entertaining treatment in this biography. Largely unknown in the U.S., his story is filled with the suspense of a blockbuster war movie, offering new and insightful perspective into the political climate of 1950s Cuba."

Washburn Review: "The Americano" is History at it's finest

Kirkus: "Another seamy mystery of the Cold War, nicely told."

AN EXCERPT FROM THE PROLOGUE OF THE AMERICANO

During the summer of 2002, Comandante Raul Nieves invited me to his duplex apartment across from the Malecon sea wall and promenade in Havana to talk about the Escambray and the Revolution.

Nieves, in his seventies now, is a little hard of hearing, which may account in part for his revolutionary shout, a tone I encountered often among Cubans who find comfort in parroting reams of official history. It's like listening to a quarreling spouse who wants his entire argument to be heard uninterrupted, hoping that some incantatory power will make what he says unquestionable.

It's also like Fidel Castro's impassioned discourses, which are ubiquitous on Cuban television. Be's not just standing there, he's always talking, delivering long lectures that, for the most part, sound nothing like the "reasonable" political speeches to which we are accustomed in the United States. Fidel argues and defends, rants and chides. He pauses to fiddle with the microphones, collects himself for a particularly salient barb aimed at some aspect of U.S. policy. Then he bounces up onto his toes, cocks his head, rolls his Rs, points his finger, accusing and justifying. Regardless of what he's saying, his passion is impressive. The modulation of his voice and his body language persuade before the ideas have come to rest in the listeners' minds. It's great drama and it's on almost every day.

The revolutionary shout of other Cubans seems to imitate the tone of Fidel's conviction, often repeating something El Com.andante en Jefe has said. Sometimes the speakers even reference their source, saying, for example, "As Fidel said about the French Revolution, ... " While the imitators can reproduce the volume, they have trouble reflecting the passion and, since they are merely sourcing their information, when they finish what they can remember they often start over from the beginning.

Nieves gnawed on an unlit cigar and listened to the quick synopsis of my research. Then he disappeared upstairs and brought back his personal archive of photos, documents, and notes on the Revolution. He was planning a book, he said, one that would tell the true story of the Escambray.

As he shuffled his papers, Nieves ignored or didn't hear my first questions about the Second National Front of the Escambray. A rooster walked through the laundry room beyond the kitchen. The Comandante laid out black-and-white photographs from 1958, '59, '60, and '61. Photographs of the Rebel Nieves showed a man who looked like a young Robert DeNiro, wiry, tough, and clearly loving the adventure of rebellion and revolution. "Faure Chomon," he said, identifying his commander and the leader of the DRE. "But who's that?" I asked, pointing at an unnamed man beside Chomon. At first, Nieves ignored me, and I thought maybe he'd forgotten the man's name. I tried again. Finally, exasperated, he bellowed in a pitch-perfect revolutionary shout, "Traidor!- Traitor!"

It soon became evident that only two categories of people existed: heroes and traitors. The heroes had names. The traitors didn't. "Who's that?" I'd ask. "Traitor!" he'd bellow. Misguided. Nothing good about them-ever. Even the things they'd done in support of the Revolution before they became traitors were erased! They mattered only as a category of people to be eliminated, and as a foil to those who had remained loyal to Castro's Revolution.

Our conversation went on from there, question and deflection, parry and riposte, like a fencing match, each of us daring the other to expose a little more of what he knew.

"The Second National Front of the Escambray never fought in a single battle. When Faure Chomon arrived in the Escambray, he realized immediately that Menoyo and his companions were traitors. He denounced them and expelled them from the DRE.

''All they did," he continued in the loud monotone, "was eat the peasants' cows, chase the peasant women, and get fat." That was it, the entire history of the SNFE according to Raul Nieves. Over the course of our two hours, I heard this version several times.

As Nieves told me about "traitors" and "comevacas-cow eaters," I peered over his shoulder at the notes he flipped through as we talked. When he noted my gaze, he turned slightly, as if to block my view, hut he did not put the papers away. In the documents, I caught brief glimpses of lists of men who fought with the SNFE and charts detailing the SNFE's battles with the Cuban Army, battles that Nieves was telling me had never happened. The notes on Nieves's dining-room table, the ones he was allowing me to catch hits and pieces of, contradicted nearly everything he was telling me. On one list, next to almost every Rebel victory in the Escambray was written the name of Morgan or Menoyo. I saw location names: La Diana, Charco Azul, Michilena, Linares, Hanabanilla, Rio Negro. The list went on.

Was he trying to protect himself and give me information at the same time? Or was he careless? Nieves never strayed from the official talking point, that the SNFE were traitors and agents of the imperialists. I had nothing on tape that would compromise him.

When we finished the interview Nieves and his wife insisted on taking me to lunch. We went to an outdoor restaurant that catered to the Cuban elite and foreign diplomats. The three of us were whisked into a mobile, aluminum storage building that had been outfitted as a dining room for special parties. There were no windows. The air conditioning whirred and I shivered as the three of us ate alone in the room. Nieves had a glass of rum, his mood darkened, and I wondered at the personal toll his distortions had exacted.